Muslims have had a working identity within Brazil for as long as slavery has existed which initially introduced the faith to the region. From this, one can see the emergence of the Brazilian-Muslim, an identity of its own, born out Brazil’s very own history of migration and slavery, as opposed to the Muslim-in-Brazil. Contributing to one of the most influential slave revolts in South American history, it is clear to see the impact that African Muslim slaves had on the journey to the emancipation of African communities and the end of colonisation. However, this history is often not remembered and the understanding of Islamic influence is not given the importance that it deserves. Official figures calculate that there are approximately 35,000 Muslims residing in Brazil, other sources show that the population reaches heights of nearly 1,500,000. With a population reportedly reaching into the millions, further discussion must be sought regarding the history of Muslims in Brazil.

The beginning traces of the Islam can be found during the 18th century with the arrival of slaves from West Africa, where the religion was already being widely practised, to the point of having established Islamic empires that spanned the Northern and Western regions of Africa. Hausa and Yoruba slaves spread Islam amongst the plantations early in their arrival to Brazil. Muslim Africans were referred to as Malê which has links to the Yoruba word, Imale, which in turn comes from the word Mali, the heart of the Islamic Mandinka empire under the rule of Mansa Musa. However, the argument has also been made that Malê derives from the Hausa malām, which comes from the Arabic word for teacher, mu’allim. [1] This derivation of 'teacher' is important in understanding the revolt as many of the African Muslims were well educated. The basis of Islam which focused on education translated into the ability of Malê scholars to take charge in the struggle for freedom.

The Malê revolt, which took place on the last Sunday of the Islamic holy month of Ramadhān, was largely influenced by Islamic thought. The revolt came as a result of forced conversions to Catholicism. Muhammad Shareef makes the argument that the revolt, as well as the mission to assist all slaves, was essentially Islamic in nature, based on the principles of freedom in Islām and fighting just wars against oppression, Jihād. [2] Though it did not end in a victory for the rebel forces, it was at the forefront of the revolts that would lead to the abolition of slavery in the region.

These principles of freedom that were established in the faith act as inspiration. The stories of the successful Haitian revolution coupled with fights for freedom in Bahia become tools to allow other African slaves to reenact the battles carried out by those peoples who had struggled in the name of equality. The essence of the Muslims of Bahia was to support the cause of emancipation, regardless of their ethnoreligious background. Through mutual-aid societies, the Malê would assist in the liberation of various other African slaves.

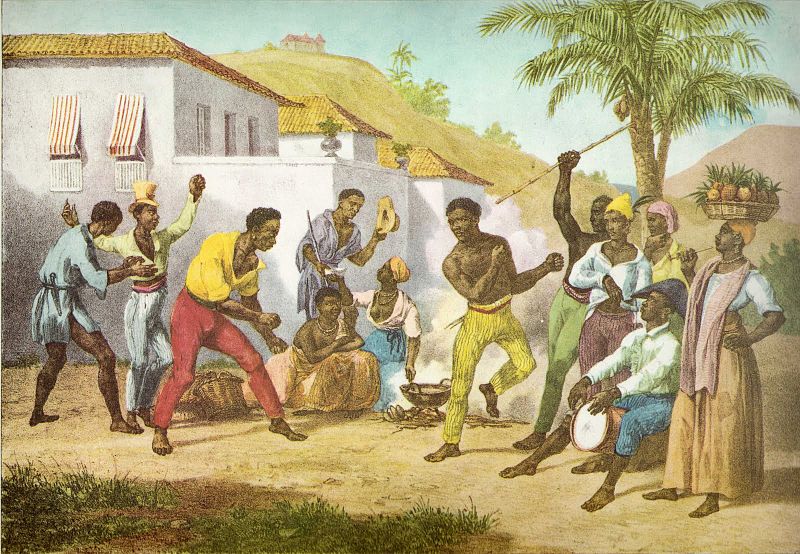

Slaves performing “Capoeira,” a Brazilian martial art, 1825

This was apparent to the Brazilian empire who initiated a greater crusade to convert the remaining slaves after the failure of the revolt to Catholicism. The spheres of influence that surrounded the other plantations would be disastrous for the economy of the country, which was built upon the backs of African slaves. The general fear that the authorities held was that the influx of slaves post-1835 would follow the example of the Malê people and conduct successful emancipation campaigns. [3] Had these greater numbers of slaves begun similar revolts, the colonials would have expected that Brazil would follow Haiti into independence.

Although forced conversions by the government had committed to subduing further revolts via Malê people, Islam was still a prominent religion amongst the African slaves with gently declining numbers until the early 1900’s. However, the reduced number of African Muslims was superseded by the increase in Arab migrants, mainly from Lebanon and other regions within the Middle East.

Muslim migrants from the Middle East also brought different sects of Islam with them. In Brazil, 90% of the Muslim population is made up of Sunni Muslims with about 10% being Shia. Muslim populations have tended to stay in the cities with a high percentage of the Muslim-Brazilian population being business owners and maintaining independent businesses and community networks. [4] And yet Islam does not appear as a rising religion even though it is the fastest-growing faith in the world. There is surprisingly little regard given to the Malê people and the acknowledgement of their role is small. This is perhaps due to the apparent failure of the rebellion, however, if one looks more closely at the long-term implications, 1835 was the beginning of the end for slavery in Brazil. The fear of greater revolt by the majority African slaves due to the influence of the events in Salvador de Bahia was the primer.

Though Brazil has developed greatly, rising as one of the forefront economic powerhouses, one can see the remnants of this colonial age once again. Although officially a secular state, there is no denying the great influence of Roman Catholicism that runs throughout the country. the practices of integration come as quite a pseudo-realistic one as there is still no accommodation for faiths outside the Catholic Church. Though there is a tolerance of other faiths, no efforts are made to accommodate said faiths. This can be seen via the latest official census with figures stated previously. The fact that many Muslims are recorded as ‘other’ and therefore not included in the Muslim statistic comes as shocking as they are pushed into even smaller minority statuses. [5] The understanding of Muslims as a major contributor in the abolition of Slavery is overlooked and the desire to keep Brazil within its Catholic traditions still dominates Brazilian culture. Though it is unfair to say that there is a call to dumb the voices of Muslims, it is clear that no effort is made in identifying the intricate details of Muslim identity, even when many Muslims in contemporary Brazil are converts.

Muslims within Brazil have had a long-standing history. One cannot deny the historic contributions of African Muslims to the early slave revolts and their efforts in leading the nation to equality and freedom for slaves. Within Brazil, Islam has been spread throughout and contributed to the livelihood of Brazilian cities for over a hundred years. The relevance of Muslims in arguably one of the most ethnically diverse regions in Latin America is important to note, as contributions to education, freedom, and social mixing has been promoted through the introduction of Muslims within Brazil and its various cities.

References:

José Reis, J (1995). Slave Rebellion in Brazil: The Muslim Uprising of 1835 in Bahia. 2nd ed. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p96.

Shareef, M (1998). The Islamic Slave Revolts of Bahia, Brazil A Continuity of the 19th Century Jihaad Movements of Western Sudan. Pittsburgh: Sankore'. p2.

Schwartz, S. (1970). The Mocambo: Slave Resistance in Colonial Bahia. Journal of Social History. 3, p313-p333.

Dias, A. (2011). The Islamic Presence in Brazil and Rio de Janeiro. Available: http://issuu.com/globalprayers/docs/dias-islamic-presence-in-brasil?e=3165689/5487854#search. Last accessed 11th Jan 2016.

Maria de Castro, C (2013). The Construction of Muslim Identities in Contemporary Brazil. Plymouth: Lexington Books. p27.

Author: Eissa Dar